Refugee and Asylum Law: Canada and the United States

In the modern world, the idea of open borders, border protection, refugee assistance, and the shared obligations of nations to look after the world’s displaced and concerned is a daily news topic in most countries. However, the rules governing these matters were decided long before the current day crisis which precipitated so much interest at present times.

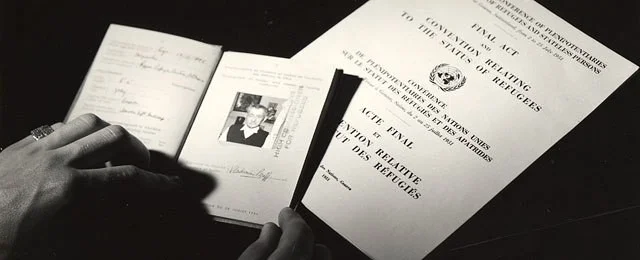

Both the United States and Canada have signed on to the 1967 Protocol to the United Nations Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees of 1951. However, unlike the United States, Canada has also signed on to the convention of 1951, along with the 1967 protocol. These international agreements stipulate the commitments of nations in upholding the rights of individuals fleeing persecution, violence and conflict. It makes up the framework which governs US and Canadian refugee and asylum law.

This article discusses both Canadian and US Refugee and Immigration Law below

Refugee and Asylum Cases in Canada

Canada’s Refugee and Asylum laws are governed by the Immigration and Refugee Protection Act of 2001(the Act). Section 3(2)(d) of the act also states the following as a major goal of the Act with respect to refugees:

“(d) to offer safe haven to persons with a well-founded fear of persecution based on race, religion, nationality, political opinion or membership in a particular social group, as well as those at risk of torture or cruel and unusual treatment or punishment;”

The refugee resettlement program is overseen by Citizenship and Immigration Canada (CIC), which manages both the processing of applications and resettlement.

There are three pathways to status in Canada through the Act which are:

The Convention Refugee Abroad Class

The Country of Asylum Class

In-Canada Asylum Applications.

The Convention Refugee Abroad Scenario:

According to Section 99(2) of the Act, “[a] claim for refugee protection made by a person outside Canada must be made by making an application for a visa as a Convention refugee or a person in similar circumstances.” This section refers to two classes of eligible refugees. The first is the “Convention Refugee Abroad Class,”comprising those who meet the definition of “refugee” in the 1951 UN Refugee Convention.

Persons in the Convention Refugee Abroad Class must be:

· outside their home country; and

· cannot return there due to a well-founded fear of persecution based on:

o race,

o religion,

o political opinion,

o nationality, or

o membership in a particular social group, such as women or people with a particular sexual orientation.

The above definition is Forward Looking, meaning that the fear is to be evaluated at the time of the application, whereby the “well founded fear of prosecution” is assessed on the basis of the reasons provided. The applicant must establish that the fear is reasonable as well, and if more than one credible fear is identified, it is the duty of the immigration officer to identify these.

Applicants must also establish that they have no reasonable prospect within another reasonable period, of a durable solution. These include the following:

voluntary repatriation or resettlement in their country of nationality or habitual residence;

resettlement in their country of asylum; or

resettlement to a third country.

Country of Asylum Class

Persons in this Class have left their home because they are seriously or personally affected by civil war, armed conflict, or massive human rights violations. Section 147 of the Immigration and Refugee Protection Regulations stipulates that:

[a] foreign national is a member of the country of asylum class if they have been determined by an officer to be in need of resettlement because

(a) they are outside all of their countries of nationality and habitual residence; and

(b) they have been, and continue to be, seriously and personally affected by civil war, armed conflict or massive violation of human rights in each of those countries.

The Country of Asylum Class is also established as a category of people eligible for refugee status under Section 99(2) of the Act as well.

An immigration officer must determine whether a person is “[s]eriously and personally affected,” meaning that “the applicant has been, and continues to be, personally subjected to sustained and effective denial of a basic human right,” by an armed conflict, civil war, or a massive violation of human rights. They must also determine whether the above has taken place using human rights reports or country condition information sources.

Application Process for Those Outside Canada:

Generally the application process begins with seeking a referral from the UNHCR or a private sponsorship organization. The local or regional UNHCR office should be contacted in order to initiate this process. After this, the applicant can submit the referral along with the application to the nearest visa office. The application process will then begin (forms are available online), with the submission of forms and etc.

Allegiance International offers advice, support and guidance for all those seeking refugee status outside Canada.

In-Canada Application

Those in Canada may also apply for protection, if they have a credible fear of persecution in their home country, and risk facing this persecution upon their return.

Section 97(1) of the Act defines a person in need of protection as:

. . . a person in Canada whose removal to their country or countries of nationality or, if they do not have a country of nationality, their country of former habitual residence, would subject them personally

(a) to a danger, believed on substantial grounds to exist, of torture within the meaning of Article 1 of the Convention Against Torture; or

(b) to a risk to their life or to a risk of cruel and unusual treatment or punishment if

(i) the person is unable or, because of that risk, unwilling to avail themself of the protection of that country,

(ii) the risk would be faced by the person in every part of that country and is not faced generally by other individuals in or from that country,

(iii) the risk is not inherent or incidental to lawful sanctions, unless imposed in disregard of accepted international standards, and

(iv) the risk is not caused by the inability of that country to provide adequate health or medical care.

People convicted of serious criminal offenses or who have had previous refugee claims denied by Immigration Canada are not eligible to make a claim in accordance with the provisions of the Act written above.

A person can apply for refugee status at a port of entry, such as an airport, or land border, or inside Canada at designated CIC offices. At ports of entry a Canadian Border Services Agency (CBSA) officer shall determine eligibility for a refugee hearing with the Refugee Protection Division (RPD) at the Immigration and Refugee Board (IRB). The RPD assesses the individual’s claim for protection. The RPD decides whether they believe the evidence provided, which is in the form of testimony, or documentary evidence, the credibility of the claimant and how much weight is to be given to evidence. Generally claims are heard within 60 days, unless a claimant is from a designated country, whereby claims may be heard faster.

Process at the US-Canada Border

According to the Canada-US Safe Third Country Agreement, which came into effect on December 29, 2004, the US is considered a “Safe Third Country,” which disallows a person from making a claim at the US-Canada border. However, there are four types of exceptions to this rule:

family member exceptions,

unaccompanied minor exceptions,

document holder exceptions, and

public interest exceptions.

Even if a claimant qualifies for one of these exceptions, he/she must still meet all other eligibility criteria or requirements.

Refugee and Asylum Law in the United States

Under section 101(a)(42) of the Immigration and Nationality Act (INA), a refugee is a person who is unable or unwilling to return to his or her home country because of a “well-founded fear of persecution” due to race, membership in a particular social group, political opinion, religion, or national origin. This definition is based on the United Nations 1951 Convention and 1967 Protocols. The United States became a party to these protocols in 1968. Congress passed the Refugee Act of 1980, which incorporated the Convention’s definition into U.S. law and provides the legal basis for today’s U.S. Refugee Admissions Program (USRAP).

There are three principal categories for classifying refugees under the U.S. refugee program:

Priority One. Individuals with compelling persecution needs or for whom no other durable solution exists. These individuals are referred to the United States by UNHCR, NGO, or they are identified by a U.S. embassy.

Priority Two. Groups of “special concern” to the United States, which are selected by the Department of State with input from USCIS, UNHCR, and designated NGOs. The groups include certain persons from the former Soviet Union, Cuba, Democratic Republic of Congo, Iraq, Iran, Burma, and Bhutan.

Priority Three. The relatives of refugees (parents, spouses, and unmarried children under 21) who are already settled in the United States may be admitted as refugees. The U.S.-based relative must file an Affidavit of Relationship (AOR) which must be processed by DHS.

In addition, individuals must generally not be firmly resettled in another country. Refugees are also subject to restrictions under Section 212(a) of the INA, including health-related grounds, moral/criminal grounds, and security grounds.

The Process:

Contact the UNHCR or an international non-profit volunteer agency for a referral. If you are unable to reach either of these, you can contact the nearest U.S. Embassy or consulate.

Next, you will be asked to complete a packet of forms. When completed, the USCIS will evaluate these forms and interview you to decide whether you qualify for refugee status in the United States. There is no application fee for refugee status.

If your refugee status in the United States is approved, your immediate family members (spouse and unmarried children under the age of 21) will be granted refugee status as well. If they are not with you at the time of your interview, they will need to file a Refugee/Asylee Relative Petition, Form I-730.

Referrals and applications received from UNHCR (and occasionally NGOs) are processed by Resettlement Support Centers (RSCs) operated by the US Department of State. Nine such centers are operated worldwide.Some refugees can start the application process with the RSC without a referral. This includes close relatives of asylees and refugees already in the United States and refugees who belong to specific groups set forth in statute or identified by the Department of State. Further, in the vast majority of cases, the UNHCR is the main source of recommendations for refugee status in the US, though very few applications may be received from NGOs as well.

Asylum in The United States

An individual seeking asylum must come to the United States seeking protection from persecution occurring due to:

Race

Religion

Nationality

Membership in a particular social group

Political opinion

Within one year of arrival in the United States, a Form I-589, Application for Asylum and for Withholding of Removal, must be filed. There is no fee to apply for asylum. Children under the age of 21 can be included in an application for asylum as well.

Individuals without a grounds for admission to the US, either through a visa or permanent residency (or other) status, may still be allowed entry at the border if they have a legitimate claim for asylum. In order to avail themselves of an asylum claim, it is imperative that the applicant at the border does not provide any false documents or information to border officials, provides all the correct identification documents, and clearly states that their purpose of arrival in the United States is to seek asylum at the time (unless a tourist visa has already been granted, whereby the asylum application can be made after entry via Form I-589 as described above).

At this stage, an immigration officer shall immediately give the applicant a credible fear interview. The purpose of the interview is to ensure that the applicant has a serious chance of winning their case, and that a fear of persecution is the basis of their claim.

If an officer finds that a person does not have a credible fear of persecution, then the applicant must request a hearing with an immigration judge, to avoid deportation. This should happen within 7 days, either in person or by telephone.

If the judge finds that the applicant has a credible fear of persecution, a full proceeding will take place in Immigration Court, before a judge, and with an attorney representing the Department of Homeland Security (DHS). At this stage, the applicant may be detained, however, they can also seek parole. Parole is most likely to be granted if the applicant can verify their identity, if they have family or other contacts in the area, if they can post a bond (money that they give up if future hearings are missed), and can maintain financial independence until a decision is made on an asylum case.

Conclusion

As it may be gathered from the above article, refugee and asylum law is far from a straightforward matter. It is more of a complex web of rules, regulations, principles and laws.

Therefore, help and advice in managing a refugee application can be of great relief to those who need or desire to pursue migration as a refugee and asylee.